Evidence of human life on the territory of present-day Turkmenistan started in the Paleolithic Era. Rock inscriptions can be seen in Jebel in the Krasnovodsk Peninsula, and various finds can be observed in the National Museum in Ashgabat. More extensive is the evidence of human settlements from the Neolithic and Eneolithic Eras: various sites in the foothills of the Kopetdag mountain range at Djeytun (near Ashgabat) and Anau (near Ashgabat) show evidence of early agricultural activity and village-like settlements.

For those with a special interest in visiting these sites please contact us directly.

The Bronze Age marked the beginning of several large oasis settlements with not only residential functions, but also ritual and burial sites, and with evidence of the existence of contacts with people from Indian, Bactrian and Mesopotamian civilizations. While remains of the Bronze Age settlement in Abiverd (near Kaahka) has largely been covered by settlements from later times, the oasis region of Margush at the previous Murghab river delta remains impressive evidence of the existence of a civilization that has recently been recognized as a fifth Bronze Age civilization next to Egypt, Mesopotamia, India and China. The civilization is referred to as the Bactrian-Margianian Civilization. Dozens of settlements from different time periods within the Bronze Age are spread around the territory where in ancient times the Murghab River flowed. Among these are Altyn Depe, Namazga Depe, Keleli, Togolok, and Ajikui.

In the late Bronze Age life in the Murghab delta oasis declined and over the next centuries concentration of habitation shifted – with the shifting of the Murghab River flow - towards the area we now refer to as Merw, a city that reached the peak of its fame under the Seljuk Empire in the 10th century.

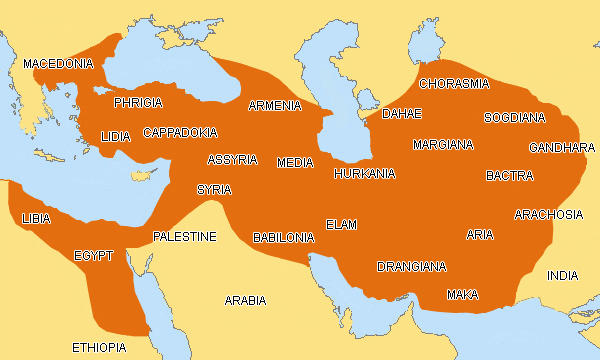

The first recorded evidence of population settlements in the Merw area was found in the Behistun rock inscription in Iran which was created in the VI c. BC when most of present-day Turkmenistan was part of the Achaemenid Empire.

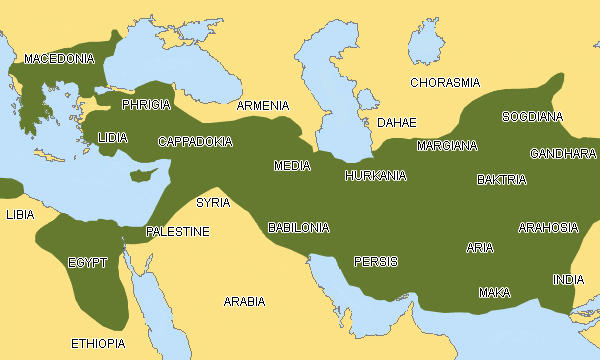

Merv under the name of Aleksandria Margiana (Erk Kala or Iskander Kala) was included in the area conquered by Alexander the Great and mentioned by a number of Hellenistic and Roman authors. The Seleucids, Alexander’s successors, founded the second city of Merv (IV c. BC), known today as Gyaur Kala, which experts identify with Antiochia Margiana.

The Seleucids and after them the Parthians and Sasanids developed Merv as administrative, cultural, trading and military center. After the battle of Carrhae thousands of Roman soldiers were sent to settle in Margiana. The Sassanid period was marked by religious tolerance and Sassanid Merv was a meeting point of many religions: Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, and Manichaeism. Under the later Sassanid kings Merv was a seat of a Christian archbishopric.

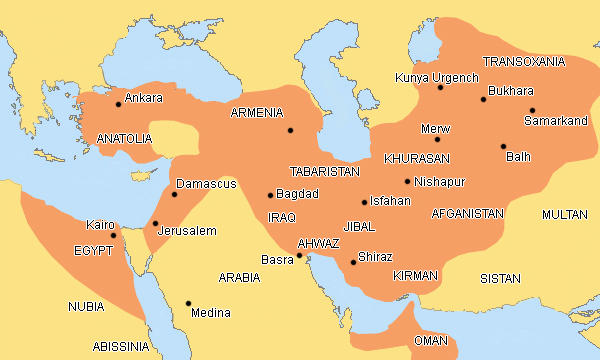

The Moslem Arabs conquered Merv in 651. They moved the city slightly to the west of the original site and made it the capital of Khorasan province. Along with Baghdad, Cairo and Damascus, it became one of the most important centers of Islam. In those days silk was being cultivated in Merv. After having been ruled by Arab khalifs, Merw was occupied by several feudal dynasties, such as the Persian Samanids and Turkic Ghaznevids.

Merv’s greatest period of glory was under the rule of the Turkic Seljuks (XI-XII cc), who occupied Khorasan and defeated the Ghaznevids near Merv in 1040, establishing their regional eastern capital here. At this time Merv was called ‘The Jewel of the sands’, ‘the Queen of the east’, and Marw al- Shahijan ‘the Soul of Kings’.

The Great Seljuk Empire extended from China to Syria and from the Oxus to Arabia. The Seljuks founded a group of dynasties in Persia, Syria and Asia Minor and were responsible for the construction of monumental buildings, notable for their elaborate ornamental brickwork and stucco decorations. They encouraged the arts, all kind of sciences, literature, and architecture. Seljuk Merv was like a magnet to many celebrated scholars, poets and writers, who worked in its legendary libraries and observatory. Among them was Yaqut al–Hanawi, who spent about three years in Merw collecting material for his geographical dictionary, and Omar Khayyam, who compiled his astronomical tables, the so-called Jalal al-Din Calendar, working in the Merv Observatory.

The talent of Omar Khayyam flourished under Malik Shakh, who owed his reputation of being the greatest of the Seljuks’ sultans mostly to the wise government of his vizier Nizam ul-Mulk. In 1092 Malik Shakh died and the empire experienced a short period of instability. The high point of the Seljuk empire was under the rule of Sultan Sanjar (1118 - 1157) and his fame eclipsed even that of Malik Shakh.

After the reign of Sultan Sanjar the power of the Seljuks began to wane. In 1221 the Mongols conquered Merv. They destroyed the city, burnt the libraries, demolished the dams and massacred the citizens. One chronicler estimated that 700,000 people were killed here. Merv never fully recovered from this disaster; however the archeological excavations at Merv indicated that Merv was not completely abandoned after the Mongols.

In the early fifteenth century the descendants of Emir Timur (Tamerlane) re-built the dams and founded a new urban center. However, Merw never got back its previous status of fame, as Emir Timur made Samarkand the capital of the Timurid Empire.

In the 18th century Merv came under the rule of the emir of Bukhara and in the 19th century the emir of Khiva conquered it. However, the Turkmen Teke tribe drove out the troops of the emir in 1836 and remained in control of the area until the tsarist Russian armies annexed Merv in 1884.

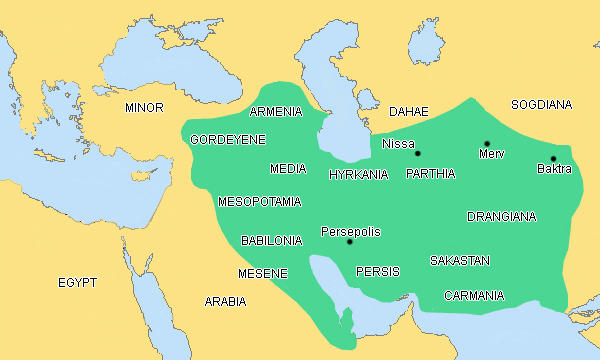

Remains of an important residential-ritual complex at Nissa dating from the second half of the III c. BC indicate the presence at the territory of present-day Turkmenistan of settlements from the time of the rise of the Parthian Empire.

The Parthian empire, also known as the Arsacid Empire, was the most enduring of the empires of the ancient Near East. A lot of information about the Parthian empire was taken from Roman and Chinese historical chronicles, whereas the Parthians left relatively little recorded references.

The first mention of Parthia we can find in Iran in the Behistun rock inscription by Dari Gistaspus. At that time Parthia was one of the satrapies of the Persian Achaemenid empire and later, after Alexander’s death – the Seleucids. In the middle of the 3d century B.C. a number of uprisings took place in Central Asia against the Hellenistic power and Parthia was the center of one of such uprisings. At the head of the biggest one was Arsaces I, who became the founder of the independent Parthian kingdom and the Arsacid dynasty.

Mithridates I of Parthia (r. c. 171–138 BC) greatly expanded the empire by seizing Media and Mesopotamia from the Seleucids. At its height, the Parthian Empire stretched from the northern reaches of the Euphrates, in what is now eastern Turkey, to eastern Iran. The empire, located on the Silk Road trade route between the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean Basin and the Han Dynasty in China, quickly became a center of trade and commerce.

The Parthians largely adopted the art, architecture, religious beliefs, and royal insignia of their culturally heterogeneous empire, which encompassed Persian, Hellenistic, and regional cultures.

With the expansion of Arsacid power, the seat of central government shifted from Nisa, Turkmenistan to Ctesiphon along the Tigris (south of modern Baghdad, Iraq), although several other sites also served as capitals.

Rome always clashed with Parthia, in particular about the control over Armenia and the Levant, considering it as the main obstacle on the Great Silk Road. In 53 B.C. the Roman general Crassus invaded Parthia. At Carrhae Crassus was beheaded by the Parthians. The Roman army was defeated and Roman prisoners were sent to settle in Margiana.

However, the Romans launched a counterattack against Parthia and several Roman emperors invaded Mesopotamia during the Roman-Parthian Wars. However, frequent civil war between Parthian contenders to the throne proved more dangerous than foreign invasion, and Parthian power evaporated when Ardashir I, ruler of one of the Parthian vassal states, revolted against the Arsacids and killed their last ruler, Artabanus IV, in 224 AD. Ardashir established the Sassanid Empire, which ruled Iran and much of the Near East until the Muslim conquests of the 7th century AD, although the Arsacid dynasty lived on through the Arsacid Dynasty of Armenia.

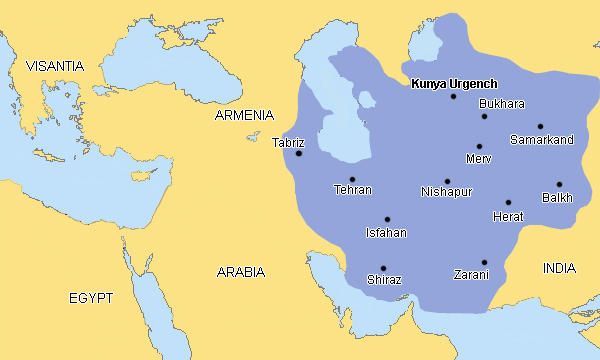

Another great empire that developed at the territory of what is today Turkmenistan, is in the region that was then called Khorezm. Kunya (Kone) Urgench was the capital of the Khorezm Empire.

The city of Biruni and Avicenna, al Farabi and al Khorezmi was located on the caravan routes which lead to the Caspian Sea and Russia. The history of Kone Urgench is closely connected with the history of Khorezm, coming through several periods of flourishing and decays:

Khwarezm, Khorezm, Chorasmia, Hualazimo as it is named by Persians, Chinese, Greeks and Arabs in different ancient reference works, are all names of one important historical region along the Amu-Darya River. The prosperity of Khorezm was built on intensive agriculture, animal husbandry and trade.

Khorezm was subjected to the Achaemenid Empire for about two centuries, in the VI-V cc BC, Khorezmian stone was delivered to Persia for the construction of Achaemenid palaces. By the V-IV cc B.C. Khorezm became an independent region, at the head of which was a king or shah. His residence was at a palace at the left bank of the Amu Darya River.

After a short period of subjugation to the Kushan Empire Khorezm again became independent. The residence of Khorezm shah was moved to the right bank of the Amu-Darya: according to al-Biruni the citadel of Kath was constructed there in 304 BC.

Until the VII c, when the Arabs brought Islam into the Central Asian region, Khorezm maintained an authority of an independent country and experienced a mixed culture of religions - Zoroastrianism, Christianity, perhaps Judaism. In the X c. Khorezm was incorporated in the Samanid Empire.

Under the Samanids Khorezm traded with the Khazaris that lived around the northern Caspian Coast and up the Volga River, and the variety of goods traded increased significantly. Dried fruit, sweets, broadcloth, carpets, brocade, boats, bows, arrows, falcons, castor oil, fish teeth etc. were available at the bazaars of Gurgandj. The residence of Samanid governor Mamun was located in Gurgandj (on the left bank of the Amu Darya River), which appeared as the northern capital of Khorezm, whereas the successors of the local Khorezm dynasty continued to reside in Kath. In 995 Mamun, who received the ancient title of Khorezmshah, was able to unite Khorezm, and Gurgandj became the only capital of the new Khorezmian state.

In 1017 Khorezm was conquered by the Gaznevids. Then the Oguz Turks came. One of the first Oguz Turkic rulers, Alp Arslan, suppressed a local rebellion and Khorezm became one of the provinces of the Seljuk Empire. A new Anushtegin dynasty of Khorezmshahs was founded in the last years of the XI c. The founder of the new dynasty was Anush Tegin - an ex slave of the Seljuk emir, who obtained a high position under Malik Shakh, promoted himself and became a governor of Khorezm.

By the XII c. Khorezm obtained independence from the Seljuks and became the largest empire of the Middle East with its capital in Gurgandj. It stretched from Iraq in the west till India in the east, from the Aral Sea in the north till the Indian Ocean in the south. After the Mongol invasion the Empire collapsed and the capital was destroyed.

In the 15th c. Khorezm was controlled by the Khans of Golden Horde. At that time Khorezm became the wealthiest and culturally most developed province of the Golden Horde and Kone Urgench experienced its second flourishing.

Ibn Batuta, a contemporary of Kutlug Timur and Turabek Khanym, visited Kone Urgench in 1333 and described it as “very beautiful, majestic and of considerable size with large and rich bazaars, wide streets and a lot of impressive buildings”.

In 1395 the power of Golden Horde came to an end. After Tamerlane’s invasion the city was partly rebuilt, but abandoned when the Amu-Darya changed its course in the 16th century.

It is clear that by far the largest number of historical sites on the territory of Turkmenistan date from the times of the Hellenistic, Parthian, Khorezmian and Seljuk empires, that thrived with the development of the Great Silk Road. Here’s a piece of history about that famous Road:

The Great Silk Route, starting from the Chinese city of Ch’ang-an (modern-day Xi’an) and leading to the shores of the Mediterranean, spanning over Asia and Europe with a total length of 7,000 km, is history today. A history of more than 2,500 years. The formal starting date of the Silk Road is connected with the year 105 BC, when the Chinese arranged a fact-finding mission and started their trek to the west. Silk became the major commodity transported along this road. For centuries, Chinese kept the secret of its manufacture, banning to take silkworm eggs out of the country.

This route from China to the West, one of the greatest trading routes in the world, was named “die Seidenstrasse”, the Silk Road, by the 19th century German explorer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen.

However, not only luxurious Chinese silk had been traveling along this road but also a great number of raw materials such as bronze and cobalt, Chinese porcelain, Venetian glass, Afghan jade, lapis lazuli and rubies, Iranian turquoise, tin and copper, Siberian furs, Arabian incense and perfumes, Indian cotton, heavenly horses, Mervian steel and melons, Egyptian papyrus and other luxuries, flowers and vegetables, moreover new thinking and ideas, arts, religions, modern technologies and other practical inventions. Some researchers suggest that the Parthian parchment inspired the Chinese to develop paper for writing, which replaced the previously used silk and bamboo.

The Silk Road was not a single road. It was an unparalleled and very complicated network of routes. Its main branches skirted north and south of the Tarim basin across Central Asia and the Iranian plateau further to the west, meeting at Dunhuang at one end and Kashgar at the other. From Kashgar southbound traffic crossed the Karakoram; westbound the Tian Shan. From Sogdiana caravans could follow either the Oxus (Amu Darya) or the Jaxartes (Syr Darya), via Khorezm and its centre of Kunya Urgench on the way to the Aral Sea and further to Russia.

But the more popular branch was a southern route, taking travelers from Dunhuang across the inhospitable Taklamakan Desert (‘to come in and never come out’), Kizilkum Desert (‘Red sands’) and Karakum Desert (‘Black sands’) to the west. The city of Bactra (the capital of the Bactria region; present-day Balkh in northern Afghanistan), which perhaps is not so familiar to modern-day travelers, was roughly in the center of the Silk Road and was also the gateway to India.

Bactra was one of the major centers of Buddhism in the time of the Kushan Empire; Buddhist influence can be found in the shape of a cave city called Ekedeshik on the Turkmen side of the border in the same geographical region.

From Bactra travelers went northwards via Serakhs or Mehne (present-day Meane), and Dandankan, and reached the key caravan city of Merv.

Other travelers approached Merv from a northern route. Coming from Bukhara, after having crossed the Oxus (which was a very difficult affair) and having had a rest in Amul (the remains of which are still visible at the suburbs of modern-day Turkmenabat), they went southwards to Merv through the formidable Karakum Desert.

From Merw, some caravans cut straight across the Kopetdag Mountains on the way to Nishapur in present-day Iran, passing by Abiverd (located between Ashgabat and Merw at the foothills of the Kopetdag Mountains in southern Turkmenistan), which in medieval times became even more prosperous than Nisa (at a similar location but close to present-day Ashgabat).

Others traveled via Dehistan (Misrian) to the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon (in present-day Iraq, and built in 129 BC). From the Iranian plateau travel went down into Mesopotamia via Dura-Europos (in present-day Syria), a city founded on the banks of the Euphrates by the Seleucids in 280 BC, and a flourishing Parthian stronghold in the first century BC.

From Dura caravans went northwest via Palmyra and Aleppo (Syria) to Antiochia and across the mountains and valleys of the western parts of modern-day Turkey all the way to the Mediterranean Sea. In different periods of time different civilizations shaped the image of these vital trade routes. The fortunes of these civilizations rose and fell with the fate of the Silk Road.

So, many centuries have been passed since its decline, but today you have a chance to rediscover the Road, to recreate its atmosphere and perhaps to gain an experience similar to that of the hundreds of thousands of traders who traveled along the Great Silk Road since ancient times.

If you are interested in visiting both well-known and less known Silk Road sites, please contact us directly. We can offer a wide variety of itineraries that follow the lesser known, more difficult to reach yet fascinating monuments that are proud reminders of the Silk Road in Turkmenistan.